The Threat of Intervention

"Now we know who the next Tito is, / Slobodan his proud name is"

The Importance and Role of Action North in the Serbian Rally Movement Aimed at Overthrowing the Slovenian Reformist Government and Democratic Processes in Slovenia

Božo Repe

Action North (“Sever”) is connected with the so-called Rally of Truth announced by the Association for the Return of Serbs and Montenegrins to Kosovo (Božur) for 1 December 1989 in Ljubljana. The date was chosen symbolically, as it coincides with the date of the formation of the Kingdom of SCS on 1 December 1918. Serbs from all over Yugoslavia were to attend the rally by train and bus. Slovenian authorities banned the rally and put strict security measures in place. In the end, only a few people gathered; mostly Serbs living in Ljubljana.

The importance of preventing this rally, which was carried out by the Slovenian militia under the codename Action North, becomes clear only when viewed in the broader context of the circumstances in Serbia and Yugoslavia. The rally took place at a time when Slovenia was under a great deal of pressure from Serbia, which included an economic blockade, i.e. one republic boycotting economic cooperation with another republic within an otherwise formally unified Yugoslav economic system. Serbia carried out the boycott selectively, namely only where it damaged Slovenia and not Serbia; the measures included boycotting the import and purchase of Slovenian products. The boycott was in full contravention of the politics of the Federal Prime Minister Ante Marković, who formally took up office in March 1989, but had begun preparing an economic reform even before that time. As soon as he took up office, he attempted to liberalize the Yugoslav economy. The purpose of Serbian politics was a dual one: to block Marković because they did not agree with his reforms; and to use rallying methods (the so-called Anti-Bureaucratic Revolution) to force the resignation of the Slovenian reformist government led by Kučan. In the latter aspect Serbian politicians collaborated with the leaders of the Yugoslav People’s Army (YPA), which viewed Slovenia’s democratization as an attempt at a counter-revolution and secession.

The foreign policy context should be outlined at this point. Western powers supported the democratization of Slovenia, which was also mentioned in the articles and news items of the most reputable media. The cause was the Trial against the Four held by the YPA, but the reasons were broader-reaching – reformist processes; the institutionalization of political pluralism (formation of the first associations); Slovenia’s European and market orientation; its ties with the neighbouring countries of Italy and Austria. The flattering assessments called Slovenia “the island of freedom”, “the socialist shop window”, “a progressive enclave that arouses the interests of reformists throughout the world, including Mikhail Gorbachev”, “the main laboratory of the new socialism of Eastern Europe” and the like. There was a growing conviction that the fate of reforms in Slovenia would shape the future of Yugoslavia. In late June 1988, Der Spiegel published an article titled “At a Crossroads” describing the conflict between Slovenia, the Yugoslav Army and the federal government. The article depicts Slovenia as an Alpine republic with a hard-working population that has created a modest welfare despite the 10 percent contribution to the Fund for the Underdeveloped (the average salary of 500 marks is twice as high as that of Serbia; unemployment is at 2.4 percent, while 8.4% of Slovenian population is generating 20% of Yugoslav income). The article also states that more than half of Slovenes believe that Slovenia would fare better outside the Yugoslav federal state, and that each third Slovene has publicly opted for withdrawing from the Yugoslav federation. Afterwards, it mentions that the leaders in Belgrade are so outraged because they are under the impression that dissidents have already assumed power in Slovenia. 1 The Wall Street Journal, an American newspaper with the largest circulation, published a lengthy article on 8 September 1988 describing Slovenia as a republic with a tendency towards capitalism and democracy (which the Army cannot stand); that many people drive a Mercedes in Slovenia; that this Yugoslav republic is much more similar to Munich than to Belgrade, while its people refer to the underdeveloped south as utter Asia and the Balkans; the income per capita is higher than in Spain and the unemployment rate is lower than in Japan; 1.7 million Slovenes have created the “wealthiest Communist patch of land in the world”. It labelled Slovenian Communists as “Jeffersonian”, and Kučan as “likely the most progressive Communist in the world”.2However, the USA and the EC strongly opposed Slovenia’s secession endeavours. Formally speaking, they strove for both: e.g. in a letter dated 19 February 1991, Helmut Kohl expressed his support of a unified Yugoslavia and his expectation that the nations and republics would develop a new form of coexistence in a democratic dialogue without the use of force.3The then American ambassador Warren Zimmermann delivered a letter to Marković from the US President George H. W. Bush dated 28 March 1991, in which he expressed his support of Marković’s reforms and emphasized that the USA did not and would not favour any national or ethnic group in Yugoslavia. He expressed his hope that the “differences between the nations will be resolved within a unified democratic Yugoslavia” and vowed that the USA would not encourage or reward those wanting to break up the state.4

Zimmermann repeated USA’s standpoint at a lecture on Slovenia and ESREL on 22 April 1991 at the Cankarjev dom Congress and Cultural Centre in Ljubljana, advising Slovenes to extend the separation deadline and do their best to create a better Yugoslavia, as Slovenia would be isolated after a potential secession. Even later, after Slovenia and Croatia had attained independence in June 1991, the USA and the EC continued to advocate the preservation of a unified Yugoslavia and threatened to not recognize Slovenia. While oscillating between democracy and the preservation of Yugoslavia, in reality the geostrategic aspect of the preservation of Yugoslavia did prevail for a few months after Slovenia and Croatia had attained independence, when the merciless war raged on between the Croats and the Serbs with ethnic cleansing on both sides.

At the time of the “Rally of Truth”, the West was quietly hoping that the YPA would introduce exceptional circumstances, discipline the Republic of Slovenia which was the only rebellious one at that time and for months afterwards, or that other forms of violent unification of the state would take place. That is why Milošević’s policy of centralizing Yugoslavia, which would make him the head of state as a sort of new Josip Broz – Tito, received support and the Anti-Bureaucratic Revolution and rallies were considered a part of the democratization processes in Yugoslavia. Zimmermann attempted to convince the federal government to allow the demonstrations in Slovenia, while saying in a talk with the President of the Presidency of the SRS Janez Stanovnik on 5 December 1989 that he hoped that Slovenia would allow the demonstrations, while showing some understanding for Stanovnik’s arguments as to why it could not do so.5

The above-mentioned Zimmermann’s viewpoint – just as many other later ones – indicates complete incomprehension of events in Yugoslavia, since Zimmermann asked for Serbs to be allowed to rally in Ljubljana after more than 40 rallies had been organized in other parts of the country and the authorities had been violently overthrown in Vojvodina, Kosovo and Montenegro.

Thus, the Slovenian-Serbian conflict centred around the announced “Rally of Truth” in Ljubljana; Slovenia was isolated in this conflict, as the federal government was powerless in stopping Milošević and also detected separatism in Slovenian politics, while Milošević and Serbia had a powerful ally in the YPA. The Slovenian-Serbian conflict was not based on national hatred, as were the Serbian-Albanian or the Serbian-Croatian conflicts. It revolved around two visions of development: a centralized one that preserved socialism, and a confederal one with a market economy and orientation towards European integrations. In the Serbian vision of a centralized Yugoslavia (“Serboslavia”) Milošević was to hold the central role, which is why his cult of personality was being built systematically, not just at the rallies. For instance, a song emerged at the very first rallies and later became a permanent feature: "Sad se narod naveliko pita,/ Ko će nama zameniti Tita,/ Sad se znade ko je drugi Tito,/ Slobodan je ime ponosito /The nation wonders,/ Who will replace Tito,/ Now we know who the next Tito is,/ Slobodan his proud name is". Moreover, the rally-goers threatened all those who would not accept such politics: "Ko nam dirne, ko nam dirne našeg Slobodana,/leteće mu, leteće mu,/sa ramena glava./Whoever touches, whoever touches our Slobodan,/his head, his head/will fly from his shoulders."

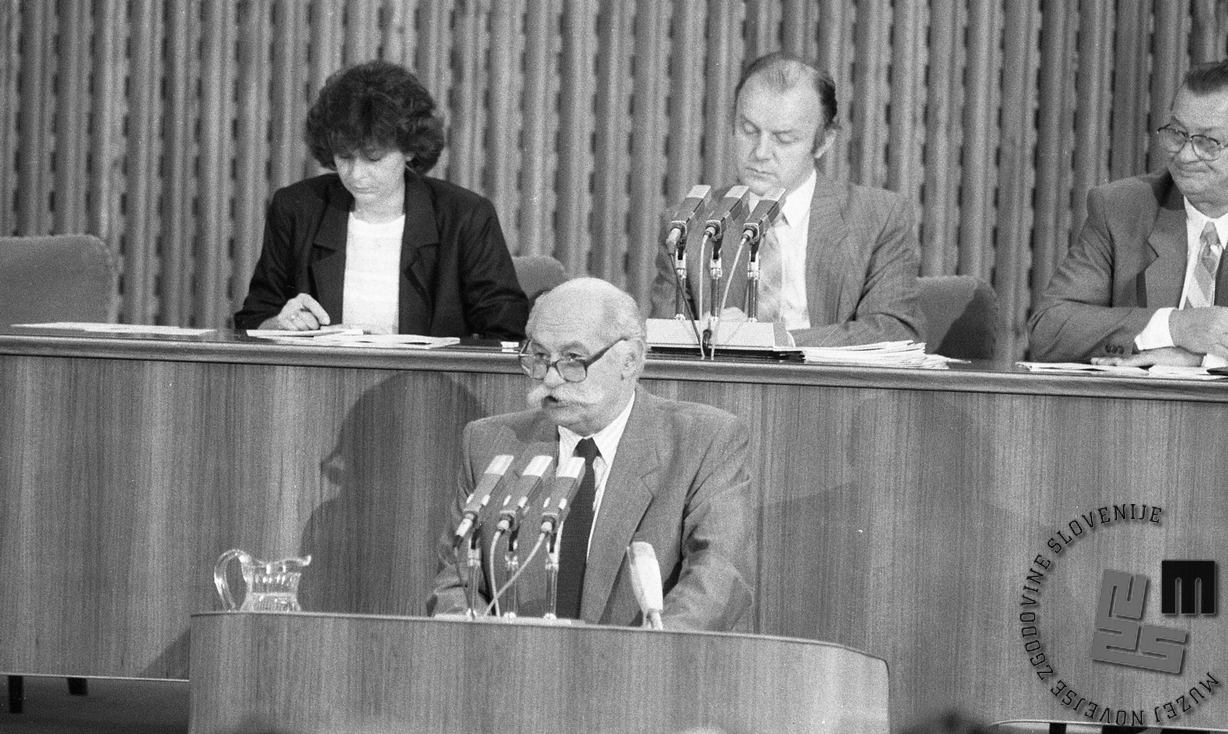

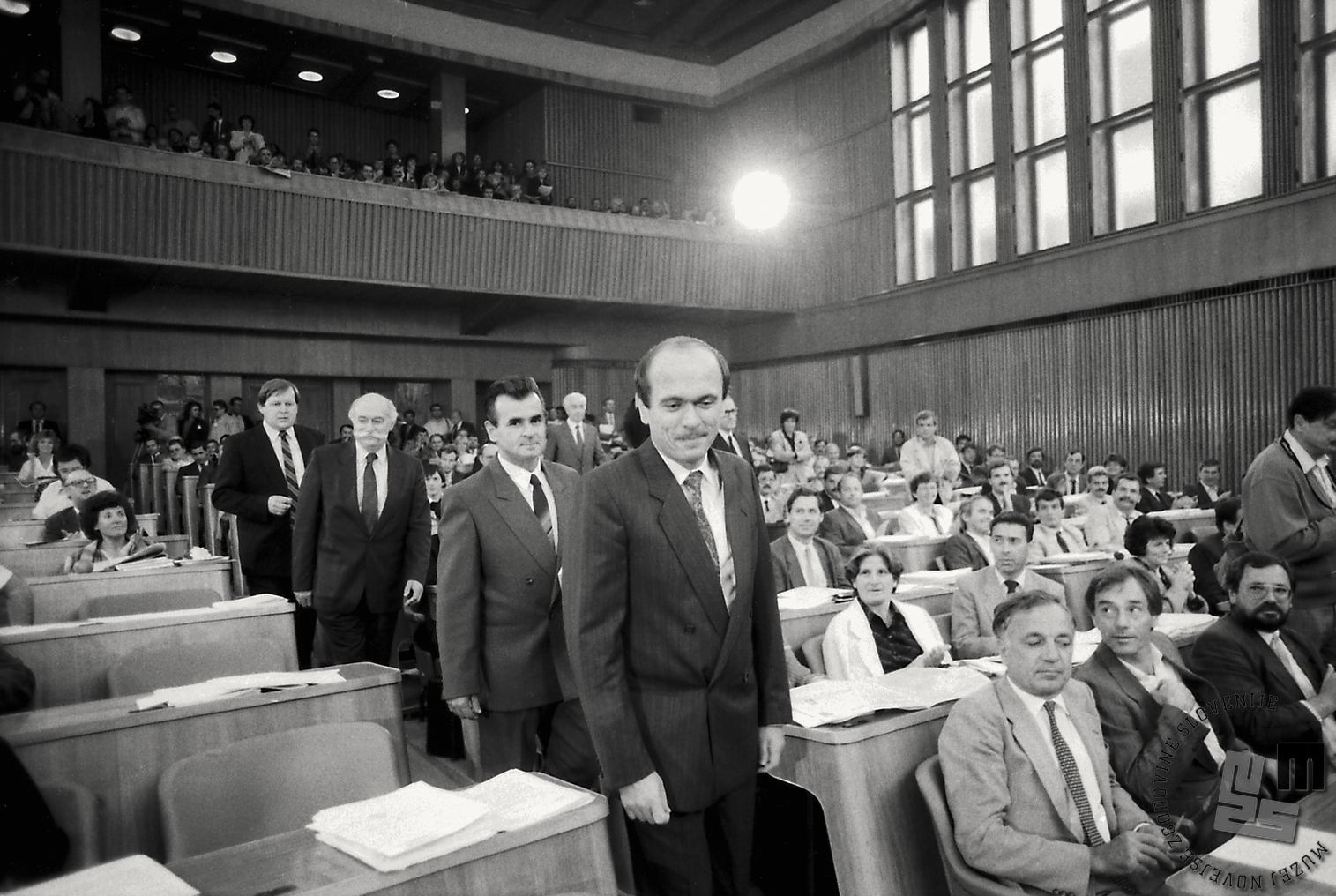

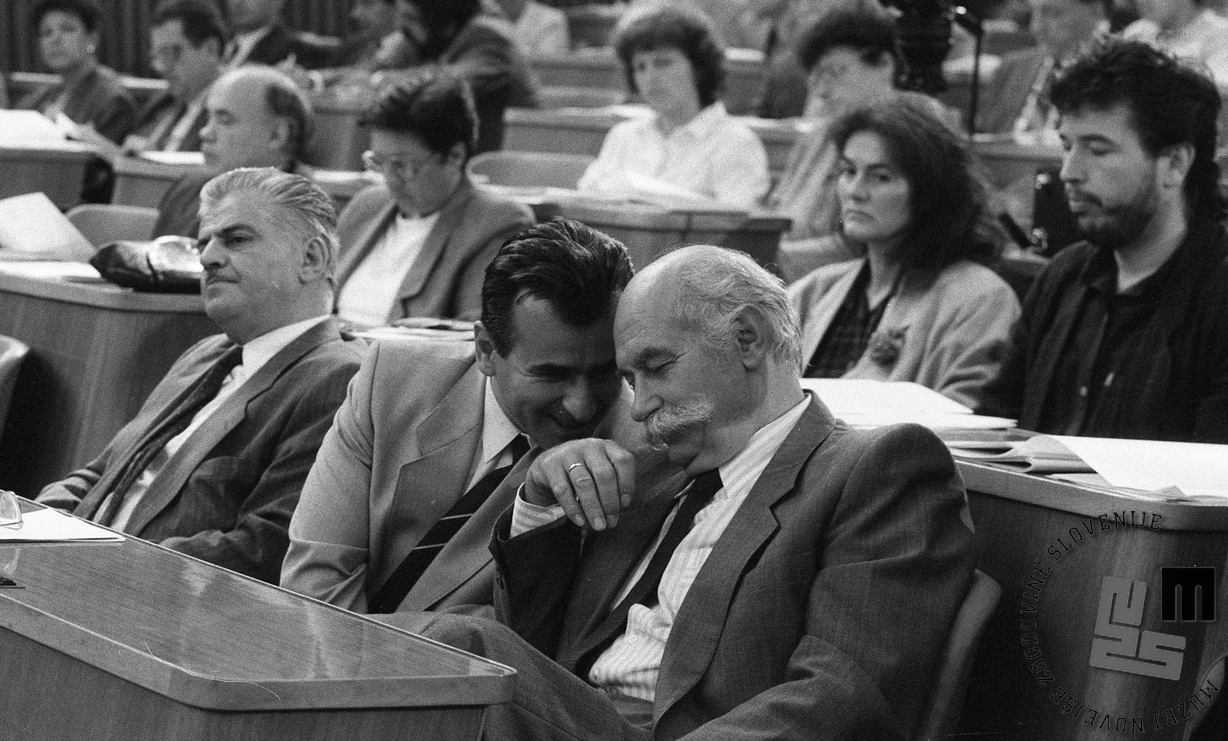

Prior to the first multi-party elections, the Serbs considered the greatest injustice to be the adoption of amendments to the Slovenian Constitution, in addition to the Trial against the Four and the assembly at Cankarjev dom, where the emerging opposition and the authorities jointly supported the Albanian miners on strike in Kosovo, who revolted against the Serbian overthrowing of constitutional autonomy. The constitutional amendments were strongly opposed by all bodies of the federal government and by the leadership of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia; they attempted to prevent their adoption at all costs; Slovenia was receiving threats of introducing exceptional circumstances since 1987, but most intensively in 1988. The amendments referring to the right to self-determination, secession and unification, and the amendments on economic sovereignty and the federation’s jurisdiction in Slovenia’s territory were especially criticized or outright rejected. Slovenia’s factual arguments and references to the fact that Serbia had altered the Yugoslav constitutional order back in February by abolishing autonomy in Kosovo and demanding that the other republics not meddle in its “internal” affairs were not heard. All federal bodies opposed the amendments and announced that trains full of protesters would be coming to Slovenia from other parts of Yugoslavia. On 27 September 1989, the amendments were adopted in the Slovenian Assembly despite all the pressures; the President of the Presidency of the SFRY Janez Drnovšek attended the solemn proclamation straight after returning from his visit to the USA. Drnovšek manoeuvred his way between the federation’s interests, which he represented as the president of the Presidency of the SFRY, and the interests of Slovenia, with the two becoming more and more incompatible.

In an alliance with Serbian political leaders, the YPA attempted to prevent the adoption of amendments to the Slovenian Constitution. The alliance had been established several months earlier, in the summer of 1989, when the Minister of Defence Veljko Kadijević, a Serbian member of the Presidency of the SFRY Borisav Jović, the President of Serbia Slobodan Milošević, and Bogdan Trifunović (vice-president of the Presidency of the CC of the League of Communists of Serbia) agreed to collaborate at a joint vacation in Kupari. Their starting point was that the YPA would defend Yugoslavia at all costs, while Serbia would provide the strongest support. In the case of Slovenian constitutional amendments, Jović and Kadijević agreed that overthrowing the state’s constitutional regime must be prevented, as the YPA had a constitutional obligation to do so and the Presidency of the SFRY was the supreme commander of the YPA. However, the army lacked the courage to impose exceptional circumstances when the constitutional amendments were adopted in Slovenia. Hence, Slobodan Milošević and the Serbian leadership took action and attempted to overthrow the Slovenian government following the well-established rally pattern.

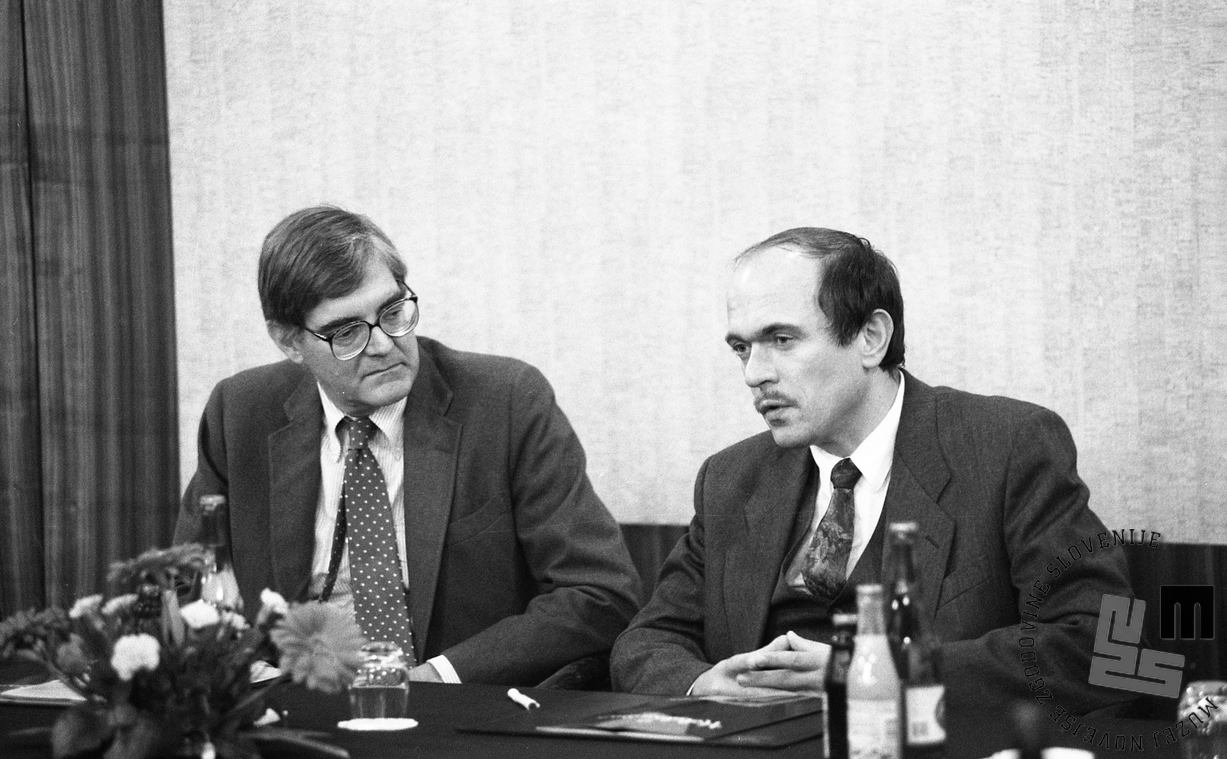

Let us illustrate the complex situation in which Slovenian politics found itself after adopting the amendments and Tomaž Ertl taking up the office of secretary of the interior at a session of the republic’s leadership. Following the adoption of the September amendments, the State Security Service analysed the circumstances in Yugoslavia and their aftermath for Slovenia, based on reports and analyses.

In light of the announced Rally of Truth in Ljubljana, which was to overthrow the Slovenian government, the reports by the State Security Service showed, quite accurately, the largest crisis centres in Yugoslavia and indicated a potential (bloody) turn of events, which indeed occurred a year-and-a-half later. Ertl assessed that Slovenia had no allies in Yugoslavia; that the so-called Western division, i.e. the hypothesis on a Byzantine south-eastern part of Yugoslavia and a progressive western part, was incorrect. In actual cases, the Croats will act as they did upon the adoption of constitutional amendments and during all other aggressive interventions in Slovenia. The so-called Croatian Spring was smothered in Croatia, but the idea is still strong; clerical nationalism, in the worst sense of the word, is on the rise; Ustasha songs are being sung more and more, since Croats consider them a symbol of the Independent State of Croatia. Croatian political leaders are engaged in trials against different-minded individuals; they are dissatisfied because Slovenian media (Mladina) are reporting about the Croatian Spring and its representatives, and about Croatian emigration. The Croatian alternative scene claims that by taking away Bosnia and Herzegovina the “belly was cut out” of Croatia. BiH is an extremely dangerous time bomb. The conflicts between Croats, Serbs and Muslims are constantly being reignited there. The situation there will differ greatly from that of Kosovo, where Albanians are facing an unfriendly state. In Bosnia the state will always be reprimanded for never taking the right side. In federal bodies, BiH delegates appear as a discordant group. Another thing characterizes Bosnia. Years ago, the people were greatly in favour of the insinuation of certain Arab states that the Muslims in Bosnia should strive for an independent autonomous state, which they would then expand into a republic, partly to the detriment of Montenegro and Kosovo; eccentric leaders, such as Khomeini and Gaddafi, judged that this would act as a springboard for the penetration of Islamism into Europe. Western Europe is not willing to acknowledge the breaking up of Yugoslavia of any kind, which is also due to a fear of the penetration of Islam. It might not be the most important one, but it is surely one of the arguments for Yugoslavia to stay as it is, instead of having five states here tomorrow and we would have to deal with each one separately ... Most of the people from other republics who are living in Slovenia are frightened and undecided. However, if those who are convinced it is their civic obligation should show tomorrow that they disagree with the Slovenian Constitution, Slovenian politics, etc. using aggressive actions, it would not take long to win such people over. They would join them in fear of being exiled from Slovenia the next day as a technological redundancy; they also fear that the chauvinism – which is getting worse every day and there is a growing number of attacks also on those who are working in our republic peacefully and honestly – would result in their gradual deportation. It would not take more than 2000, 3000 people to organize a march.”6

At first, the rally politics developed independently of Milošević in Kosovo.7Its initiator and main organizer, and later the “exporter” of the so-called Anti-Bureaucratic Revolution was Miroslav Šolević. He hailed from the Serbian Resistance Movement (Srpski pokret otpora – SPO), a group that had formed following the Albanian demonstrations in Kosovo in 1982 and made its first public appearance in the same year, visiting politicians and organizing protests. They accused the authorities in Belgrade, both Serbian and federal, of leaving Kosovo to the Albanians. On 26 February 1986, hundreds of Kosovo Serbs, with help from Miodrag Trifunović, the president of the Federal Chamber, forcibly entered the Federal Assembly and, according to their definition, “opened it to the people” (the same practice was later used by striking workers from Borovo and Uljanik). They were received by the then President of the Presidency of the SFRY Lazar Mojsov at the Sava Centar centre in Belgrade on a separate occasion. They held several mass protests in Kosovo Polje; when one of the organizers of the Serbian Resistance Movement, Kosta Bulatović, was imprisoned, 20,000 people protested in Kosovo Polje, forcing the Kosovo authorities to let him go, which is why they threatened to come to Belgrade and demand their replacement. Milošević first came into contact with them on 17 April 1987 when visiting Kosovo. During his visit he was to avoid the Serbian settlements because the authorities feared demonstrations. Members of the SPO nevertheless made contact with him because of a professor at the University of Pristina, Zoran Grujić, who was associated with the SPO, which is why the police interrogated him and hundreds of people gathered in front of his house to show support. A meeting was arranged, to which he was to arrive with Azem Vllasi, the president of the regional League of Communists. The meeting was held on 24 April 1987 in the afternoon at the primary school in Kosovo Polje, a municipality in the suburb of Pristina inhabited by Serbian population. The SPO came prepared; it organized its own speakers and demonstrations, which were attended by around 15,000 people; they had granite setts at their disposal. Chaos and a clash with the police ensued; Milošević intervened by saying that they were not to be beaten. He then suggested that the protesters choose their speakers and the rally lasted all night long. “Milošević held two speeches. The first one was given inside the building and was half-hearted. When he came out of the building, he saw thousands of people fighting the police and he said, frightened: "No one is to beat you!" He held two speeches in Kosovo Polje: the first speech inside the hall was half-hearted... When he went out of the building, when he saw thousands of angry people fighting the police, he uttered, frightened: "No one is to beat you!” He was as white as a sheet. He was afraid; the setts were flying; he would be beaten too… Comrade Sloba was created thanks to our resistance…” 8

The Kosovo Serbs later bragged about “saddling the horse” for Milošević. They eventually parted ways, but only after collaborating with him intensively and probably decisively aiding him in setting up a system of “anti-bureaucratic revolutions” with which he intended to seize power in Yugoslavia. On 9 July 1988, they began an “anti-bureaucratic revolution” in Novi Sad in Vojvodina. The rallies then spread “spontaneously” throughout Vojvodina. They began in Vojvodina in October 1988 in Bačka Palanka, led by Mihalj Kertes. They climaxed in Bačka Palanka on 4 October when 150,000 people gathered. Their leader became (Mihály Kertész), the secretary of the District Committee of the League of Communists Novi Sad. From Bačka Palanka the rally-goers marched on Novi Sad and in the so-called Yoghurt Revolution (at the rally in front of the building of regional authorities the rally-goers threw yoghurt at the small militia that was no match for their onrush) they succeeded in replacing the autonomist government of Vojvodina, which resigned on 6 October and was replaced by followers of Milošević. This model was then applied in Montenegro where the first rallies occurred soon after those in Vojvodina had begun, in August 1988. The day after the Vojvodina government was overthrown, they attempted to do the same in Titograd but were booed during the demonstrations. In the months that followed, Montenegro became divided into Milošević’s followers and opponents; as regards politics, the Montenegrin government was mainly composed of members of the older generation, while young people joined Milošević’s movement and on 11 January 1989 held a massive rally at which a third of the republic’s population gathered, forcing the Montenegrin government to resign. The leading role was taken up by the “beautiful and smart” Milo Đukanović and Momir Bulatović. (They later parted ways; Bulatović, who died in 2019, had joined Milošević, whereas Đukanović started advocating Montenegro’s independence and is still in power today.) An “anti-bureaucratic revolution” was unsuccessfully attempted in the nationally divided Bosnia and Herzegovina, where Serbian politicians claimed that Serbs could not live together with other nations.

To prevent the “Rally of Truth” which was planned in Ljubljana, the militia was directly engaged to defend Slovenia for the first time, with consent from the political leaders. Milošević’s propaganda machine went after Slovenia based on the tried-and-tested hypothesis that the Slovenian government was not in control of the situation and therefore had to be replaced or overthrown. The main organizer of the Anti-Bureaucratic Revolution, Miroslav Šolević, pledged after the assembly at Cankarjev dom in February 1989 that he would organize a protest rally on 25 March 1989 in Ljubljana. The first organization of a rally in Ljubljana was planned even earlier, during the rally wave in the summer and autumn of 1988, but its organization would have taken much preparation and the most important goal of the organizers at that time was to discipline “Serbian” territories. So, another attempt was made on 1 December 1989 but was strongly opposed by the Slovenian authorities, the State Security Service and the Slovenian militia with a well-organized action called North, even at the cost of a potential conflict and bloodshed, although they wanted to avoid that as much as possible. The political decision to ban the rally was adopted with a decision from the Presidency, and later the Assembly, on the grounds of the statutory power of protecting law and order.

Slovenia was in a very weak position at the time; it had virtually no allies in Yugoslavia. Even though the Yugoslav legal system was becoming increasingly chaotic from the Constitutional Court downwards, with the legislation either observed or not as one saw fit, and an Anti-Bureaucratic Revolution or “the happening of the people” was underway, Slovenia wanted to remain consistently legalistic, enacting changes at home and in Yugoslavia by legal means, without resorting to violence. That was its main instrument in the process of strengthening its independence and democratization ever since the so-called Trial against the Four. Decisions regarding Action North were also made in this manner. The application filed by the organizers was first rejected by the Ljubljana City Secretariat of the Interior on 20 November 1989. The order was issued pursuant to Article 12 of the Public Assemblies and Public Events Act based on the assessment that judging from the application the assembly would most likely involve activities that do not comply with the law and whose purpose is to break up the brotherhood, unity, and equality of the nations and nationalities of Yugoslavia, and instigate national hatred and intolerance, and that such activities would not only disturb law and order, but would also lead to violence. On 22 November 1989, the contents of the order were made known to all chambers of the Assembly of the SRS, which supported the Secretariat’s decision and tasked the competent bodies in the Socialist Republic of Slovenia to adopt all measures necessary to prevent this rally, thus ensuring the safety of citizens and the sovereignty of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia. They also pointed out that in accordance with the Constitution of the SFRY any order issued by a competent body in one republic shall apply throughout the territory of the SFRY and expressed their expectation that all competent bodies in the territory of the SFRY will act accordingly and do everything in their power to prevent an organized march of rally-goers on Ljubljana. On 27 November 1989, the Presidency of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia followed suit, determining that the events in Kosovo and a few other parts of the SFRY have created circumstances that require the taking of measures referred to in paragraph 1 of Article 12 of the Internal Affairs Act for protecting law and order, people’s lives and their property. The Presidency also based its actions on the opinions of the Council for the Protection of the Constitutional Order led by Andrej Marinc, which discussed the situation in Yugoslavia and the consequences of a potential rally on two occasions. In accordance with the decision of the Presidency of the SRS, the Executive Council of the Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia likewise adopted a decision on 27 November 1989, authorizing the republican secretary of the interior to take the necessary measures to ensure safety.

The republican secretary was able to decree restricted or prohibited movement in certain areas and the meeting of citizens in public places to prevent an organized arrival to the rally and its execution. In light of the aforementioned decisions and pursuant to the Internal Affairs Act (1980, 1988, 1989), the republican secretary of the interior also issued orders prohibiting the movement of all persons headed for public assemblies or events that have been banned by an order from the Republican Secretariat of the Interior; prohibiting the traffic of all motor vehicles transporting persons headed for public assemblies or events; and prohibiting citizens from meeting in public places and at public events. Action North was then carried out on those grounds; it involved all units of the State Security Service and the militia throughout the republic.

The ban on the rally and the efficient deep coverage of the entire Slovenian territory carried out by the police, including the plans for where the rally-goers would be taken should they arrive in Slovenia by train and bus, took even the YPA by surprise. It was the first and obvious sign that Slovenia was willing to defend itself. But the YPA did not learn its lesson and continued to underestimate Slovenia, as became clear later on in the Ten-Day War.

The point of Action North was to prevent an attempt to replace the reformist Slovenian government with instigated masses from other republics. If the government were to fall, so would the newly emerging opposition and the organized, concerted democratization would be over.

Of course, no historical tale, no matter how unambiguous, has come to an end in Slovenia. As the attainment of independence wiped the slate clean for right-wing politics, particularly for Janez Janša, this tale has no political ending. Polemics ensued; conflicts regarding the founding and memorial dates, and, consequently, regarding which veteran organization was the “right” one; the establishment of the Manoeuvre Structure of National Protection Forces (Manevrska struktura narodne zaščite – MSNZ) was being highlighted as the “first defence act”. The National Protection Forces (Narodna zaščita) existed until 1990, which stemmed from the tradition of World War II resistance (a sort of urban guerrilla force); according to the concept of the General People’s Defence (Splošna ljudska obramba – SLO) and social self-protection, it would be tasked with protecting facilities and ensuring law and order in the hinterland of the battlefields in times of war. In 1990, the idea arose that the National Protection Forces would be used to formally comprise the emerging Slovenian Armed Forces. It was called the Manoeuvre Structure of National Protection Forces (MSNZ). It was to operate as a sort of illegal combination of police forces and Territorial Defence forces (in which the new Slovenian authorities secretly battled to take control and probed to find out who would be willing to follow them); the MSNZ was to operate in the interim period until the Slovenian authorities would formally take control over the Territorial Defence. Thus, a secret organization was formed within the Territorial Defence. The MSNZ was formally approved at a meeting of the Executive Council on 14 September 1990. Only then did Milan Kučan as the president of the Presidency of the Republic of Slovenia learn about it due to Janez Janša’s distrust. In the newly composed history, Action North was to be marginalized and the MSNZ was to play a central role in the initial defence of Slovenia. The ideological struggle regarding this matter has been taking place ever since the attainment of independence; it is connected with the role of individual veteran organizations in society and how certain individuals are judged (the Republican Secretary of the Interior Tomaž Ertl, who carried the weight of the action, has been demonized, which was especially noticeable when he was awarded the Silver Order for Merits).

- Archival Sources

- Arhiv predsednika Republike Slovenije/Archives of the President of the Republic of Slovenia (now kept by Arhiv Republike Slovenije/Archives of the Republic of Slovenia)

- Newspaper Sources

- “Jugoslawien: Im Abwind.” Der Spiegel, 27 June 1988, 121–122.

- Delo, 9 September 1988, 20.

- Newman, Barry. “Slovenes Acquire Taste For Living Life Well, But Party May Be Over.” The Wall Street Journal, 8 September 1988, 7-8.

- Websites

- Ast, Slobodanka. “Intervju z Miroslavom Šolevićem. Režim nas je iskoristio./Interview with Miroslav Šolević. The Regime Used Us.” Accessible at: https://www.vreme.com/arhiva_html/454/11.html (retrieved: May 2020).

- Literature

- Libal, Michael. Limits of Persuasion, Germany and the Yugoslav crisis, 1991—1992. Westport (Connecticut); London: Praeger, 1997.

- Repe, Božo. Jutri je nov dan. Slovenci in razpad Jugoslavije./Tomorrow Is a New Day: Slovenes and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia. Ljubljana: Modrijan, 2002.

- Repe, Božo. Milan Kučan, prvi predsednik./Milan Kučan, the First President. Ljubljana: Modrijan, 2015.

- Tasić, Predrag. Kako sam branio Antu Markovića./How I Defended Ante Marković. Skopje: Mugri 21, 1993.

1. “Jugoslawien: Im Abwind.” Der Spiegel, 27 June 1988, 121–122.

2. Newman, Barry. “Slovenes Acquire Taste For Living Life Well, But Party May Be Over.” The Wall Street Journal, 8 September 1988, 7-8. See also the report by Uroš Lipušček on the article “Slovenia – A Rich Communist Patch of Land” in Delo, 9 September 1988, 20. See also: Repe, Božo. Milan Kučan, the First President. Ljubljana: Modrijan, 2015, 126–127.

3. Libal, Michael. Limits of Persuasion, Germany and the Yugoslav Crisis, 1991—1992. Westport (Connecticut); London: Praeger, 1997, 6.

4. Tasić, Predrag. Kako sam branio Antu Markovića. Skopje: Mugri 21, 1993, 89.

5. Archives of the President of the Republic of Slovenia (now kept by the Archives of the Republic of Slovenia), Translation of the talk between the President of the Presidency of the SRS Janez Stanovnik and the US Ambassador in the SFRY, Mr Warren Zimmermann, 5 December 1989. See also Repe, Božo. Jutri je nov dan. Slovenci in razpad Jugoslavije./Tomorrow Is a New Day: Slovenes and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia. Ljubljana: Modrijan, 2002, 228.

6. Archives of the President of the Republic of Slovenia, Transcription of the 71st session of the Presidency of the SRS, 6 October 1989, p. 11, debate by Tomaž Ertl.

7. Ast, Slobodanka. “Interview with Miroslav Šolević. The Regime Used Us.” Accessible at: https://www.vreme.com/arhiva_html/454/11.html (retrieved: May 2020).

8. Ibidem.