Božo Repe

The 1980s were one of the most pluralist periods in the history of Slovenia, even though a one-party system was formally still in place. Many strong civil society movements (pacifistic, anti-nuclear, ecological, and others) were characteristic of that period. In 1988, during the so-called Trial of the Four, the largest civil society organisation – the Committee for the Defence of Human Rights, headed by Igor Bavčar – was established. These judicial processes were possible because they coincided with the establishment of the reformist line within the leadership of the League of Communists, led by Milan Kučan as of 1986. The reformed League of Communists no longer ignored the opposition’s ideas but attempted to implement them in the context of the Socialist Alliance of the Working People (the SZDL) as the successor of the former Liberation Front. The opposition movements were to be formalised within the SZDL in the form of a coalition. Such policy later allowed for a soft transition into a multi-party system and ensured that a consensus about the fundamental issues of the national programme was reached.

On 27 February 1989, the Yugoslav circumstances caused the opposition and the authorities to appear together at an assembly in the Cankarjev dom cultural and congress centre (the Cankar Centre) in support of the miners who were on strike in Kosovo (some 1300 miners in possession of considerable amounts of explosives protested the adoption of the new Serbian constitution that rescinded the Kosovar autonomy; the strike lasted from 4 to 27 February, when a state of emergency was declared in Kosovo). This led to an attempt at a joint formation of a national programme by the opposition and the authorities. On 3 March 1989, the Coordination Committee of the Cankar Centre Assembly Organisers became operational. Under its auspices, the representatives of the opposition and socio-political organisations attempted to draw up a political programme. Several drafts were written, mostly by the writer Miloš Mikeln. However, as the committee failed to reach a consensus, two programmes were created: the May Declaration of 1989 and the Charter of Slovenia. Already more than a year earlier – when the discussion of the amendments of the federal constitution had begun (with the intention of altering the economic system yet also assigning more power to the centre) – a constitutional opposition had formed as well. A milder version of the federal constitutional amendments had been adopted in 1988 and confirmed by the Slovenian Assembly as a compromise. However, the amendments of the Slovenian constitution had started to be drafted as well. The Slovenian Assembly adopted them in September 1989 to increase the Slovenian sovereignty and prevent the introduction of a state of emergency in Slovenia, planned by the Yugoslav People’s Army. The simultaneous deletion of the provision on the leading role of the League of Communists of Slovenia, which allowed for the formal establishment of alternative political parties, was crucial for the development of political pluralism and introduction of a multi-party system. The Yugoslav leadership described this as a counter-revolution, while the Yugoslav Army command prepared a new plan for the subjugation of Slovenia. However, the opposition kept gaining momentum in the other republics as well, and it was no longer possible to prevent a multi-party system in one form or another. In light of the conflict between the centralist and confederate system of Yugoslavia, a multi-party election for the Federal Assembly was planned for the autumn of 1990. According to the centralist plan, drawn up mainly by Slobodan Milošević with the support of the Yugoslav People’s Army, the Federal Assembly was to become the sole or at least the main assembly and dominate the Assembly of Republics and Provinces, which ensured the national equality. The Federal Assembly elections took place according to the “one person one vote” principle, which means that, due to the structure of the Yugoslav population, the Serbs held a relative majority. In the Assembly of Republics and Provinces, however, all the republics had an equal number of votes, while both of the autonomous provinces had somewhat fewer votes. The two Assemblies were equal, and it was impossible to alter the foundations of the Yugoslav system without the agreement of them both. If the concept of “one person equals one vote” prevailed, the Yugoslav majority would also make decisions regarding the state system and the secession of the individual republics. Should Slovenia fail to take appropriate measures before that moment, it would remain a part of a centralist Yugoslavia. Due to the swift dissolution of Yugoslavia, federal elections never took place, even though some politicians did in fact start preparing for them – particularly the last Yugoslav Prime Minister Ante Marković, who, to this end, established his own party and the Yutel television station. All the republics, however, organised multi-party elections, in which all-Yugoslav parties did not participate, or they merely played a symbolic role.

Slovenia was the first republic to opt for a multi-party system and a multi-party election. Towards the end of 1988, when the Trial of the Four that had encouraged a mass all-Slovenian movement started losing its political momentum, the Committee for the Defence of Human Rights faced the question of whether to keep pursuing its activities as a political party. Such a concept was implemented, for example, by the Croatian opposition, which established the Croatian Democratic Union under the leadership of Franjo Tuđman and won the spring election. The Committee for the Defence of Human Rights, however, was too heterogeneous to implement such a concept. At this time, the formation of associations (predecessors of political parties) already started. They were called associations because the legislation did not permit political parties, while associations were indeed allowed as long as they were included in the SZDL. The variety of movements within the Committee for the Defence of Human Rights thus joined the various emerging associations, which later transformed into political parties. Therefore, the initial list of associations was very diverse. Apart from the Slovenian Peasant Union (Ivan Oman) and Slovenian Union of Peasant Youth (the former was formed in the context of the Socialist Alliance of the Working People, while the latter was established in the framework of the Socialist Youth League of Slovenia), which had been established as professional organisations as early as on 12 May 1988, the following associations were established in 1989: on 11 January, the Slovenian Democratic Union (Hubert Požarnik); on 16 February, the Social Democratic Association of Slovenia (France Tomšič); on 10 March, the Slovenian Christian Social Movement (Peter Kovačič); on 31 March, the Civic Green Party (Marek Lenardič); on 5 June, the Yugoslav Union (Matjaž Anžurjev); on 11 June, the Green Movement (Dušan Plut); on 21 September, the Association for Yugoslav Democratic Initiative (Rastko Močnik); as well as certain other groups (e.g., the Group 88, headed by Franco Juri, and the Debate Club 89, both of which later merged with the Socialist Youth League of Slovenia). The more short-term and exotic organisations included the following, for example the Academic Anarchic Anti-Union (13 January 1989), the Workers’ Union, and the Anti-communist Union. The Student Cultural Centre Association and the Slovenian Students’ Union were registered as well.

The newly-created associations entered the political life with a range of programmes: some of them emphasised the issue of democracy in particular; while others underlined the question of the nation and/or built their political image on anti-communism. In this initial division of the Slovenian political space, the Slovenian Democratic Union, which managed to include a significant part of the opposition’s intellectual potential in its ranks, was the most politically influential organisation on the side of the opposition.

The trade union movement – especially the part that the Slovenian Democratic Party came from – developed in a particular manner. On 15 December 1987, France Tomšič founded the first independent trade union. This happened a few days after the workers strike in the Litostroj Factory in Ljubljana and the protests in front of the Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia. Simultaneously, he also tried to establish the Social Democratic Union of Slovenia (which was to be headed by France Bučar), but his attempt failed. The party was therefore not founded until February 1989, even though a draft of the programme had been adopted by the initiative committee earlier, on 15 December 1988.

After the opposition and the authorities had presented their viewpoints separately with the May Declaration of 1989 and the Charter of Slovenia, the dialogue between them remained open and became more intense in September 1989. The Coordination Committee of the Cankar Centre Assembly Organisers, which formally still existed, was renamed as the Round Table of Political Entities in Slovenia (usually referred to as Smole’s Round Table after Jože Smole, president of the SZDL). This decision was adopted at the 9th (last) meeting of the Coordination Committee on 11 September 1989. The Round Table, however, was established at the meeting of 22 and 23 September (when temporary rules of procedure were adopted as well). A day earlier, its establishment had been confirmed by the Presidency of the Republican Conference of the SZDL. The Round Table was to reach an agreement on the realisation of a multi-party election. Another option was to adhere to the Polish model and divide the parliament seats between the opposition and the authorities in advance until the first multi-party election, but this initiative did not prevail.

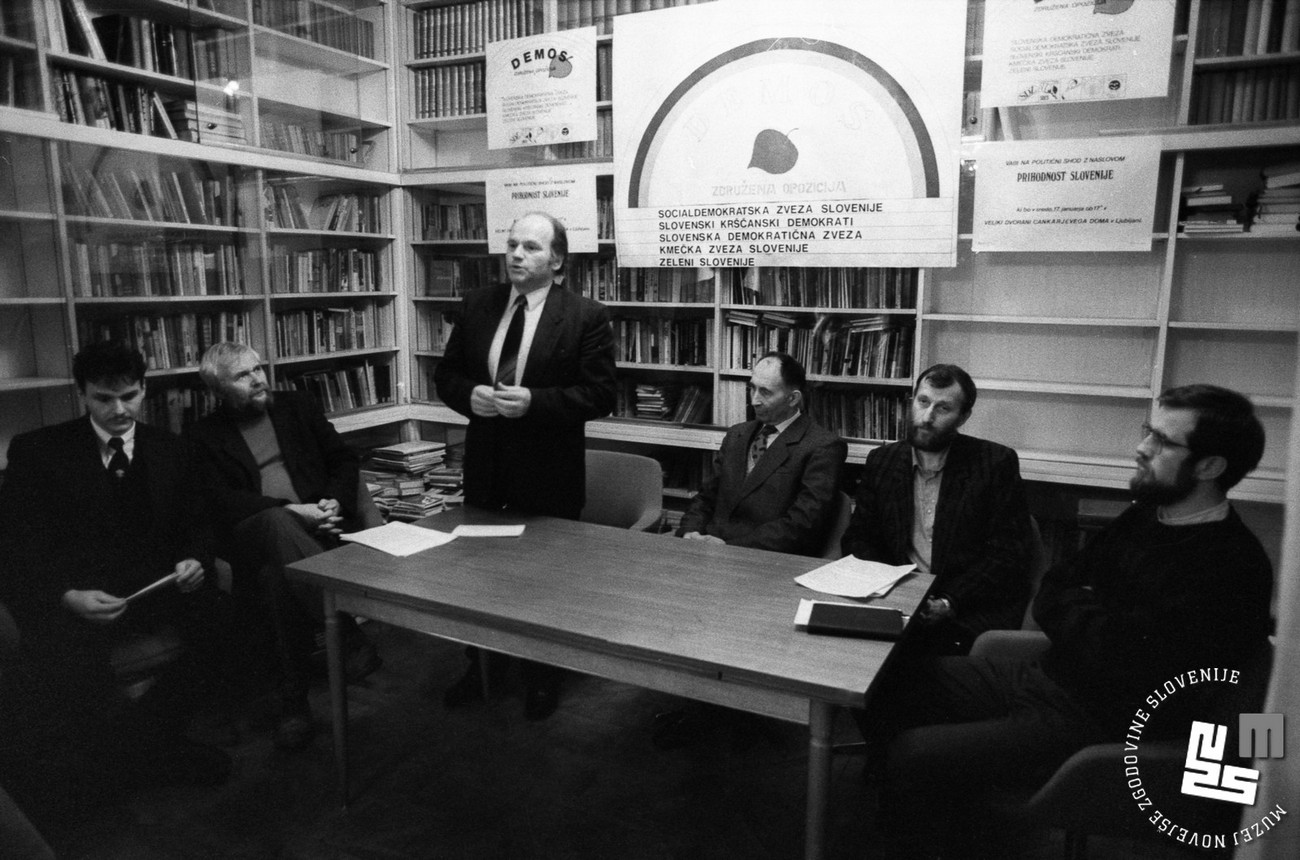

The opposition was increasingly convinced that the authorities wanted to outsmart it with the Round Table, and therefore a part of the opposition summed up its outlooks on the election with the statement “What sort of election do we want?” and expressed its doubt about the good intentions of the authorities in the text “Why we no longer wish to take part in such a round table”. The Round Table thus dissolved. Two weeks after its dissolution – after it had been abandoned by the Slovenian Democratic Union, the Social Democratic Association of Slovenia, the Christian Social Union, and the Slovenian Peasant Union – the associations of peasants, social democrats, and democrats (and later also the newly-established Christian Democrats stemming from the Christian Social Union) started discussing the formation of a joint pre-election coalition. After lengthy negotiations, this in fact took place on 27 November 1989, initially according to the “three plus one” system (the Slovenian Democratic Union, the Social Democratic Association of Slovenia, the Christian Democrats, and the Slovenian Peasant Union, which supported the joint programme yet intended to participate in the election with an independent list of candidates).

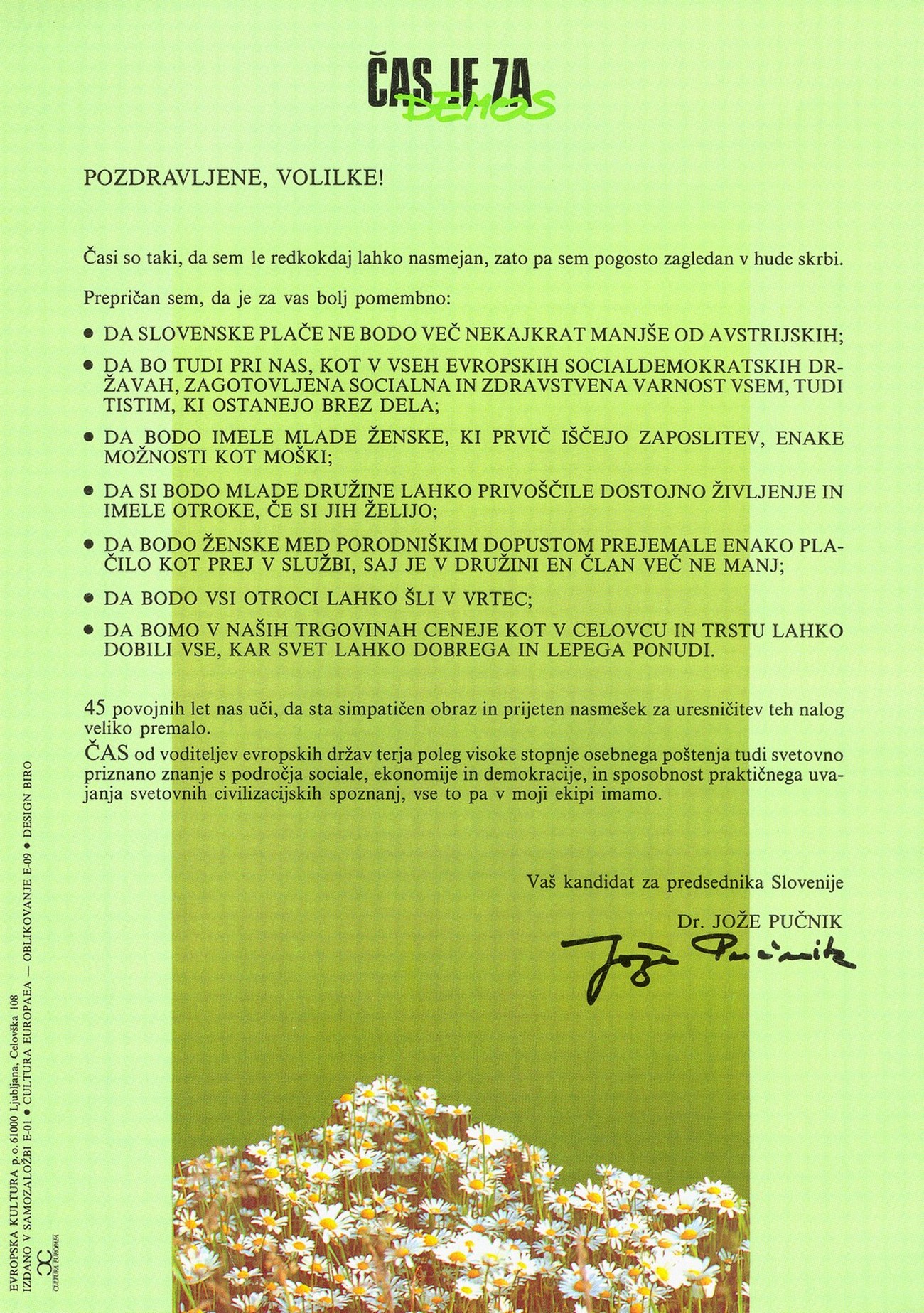

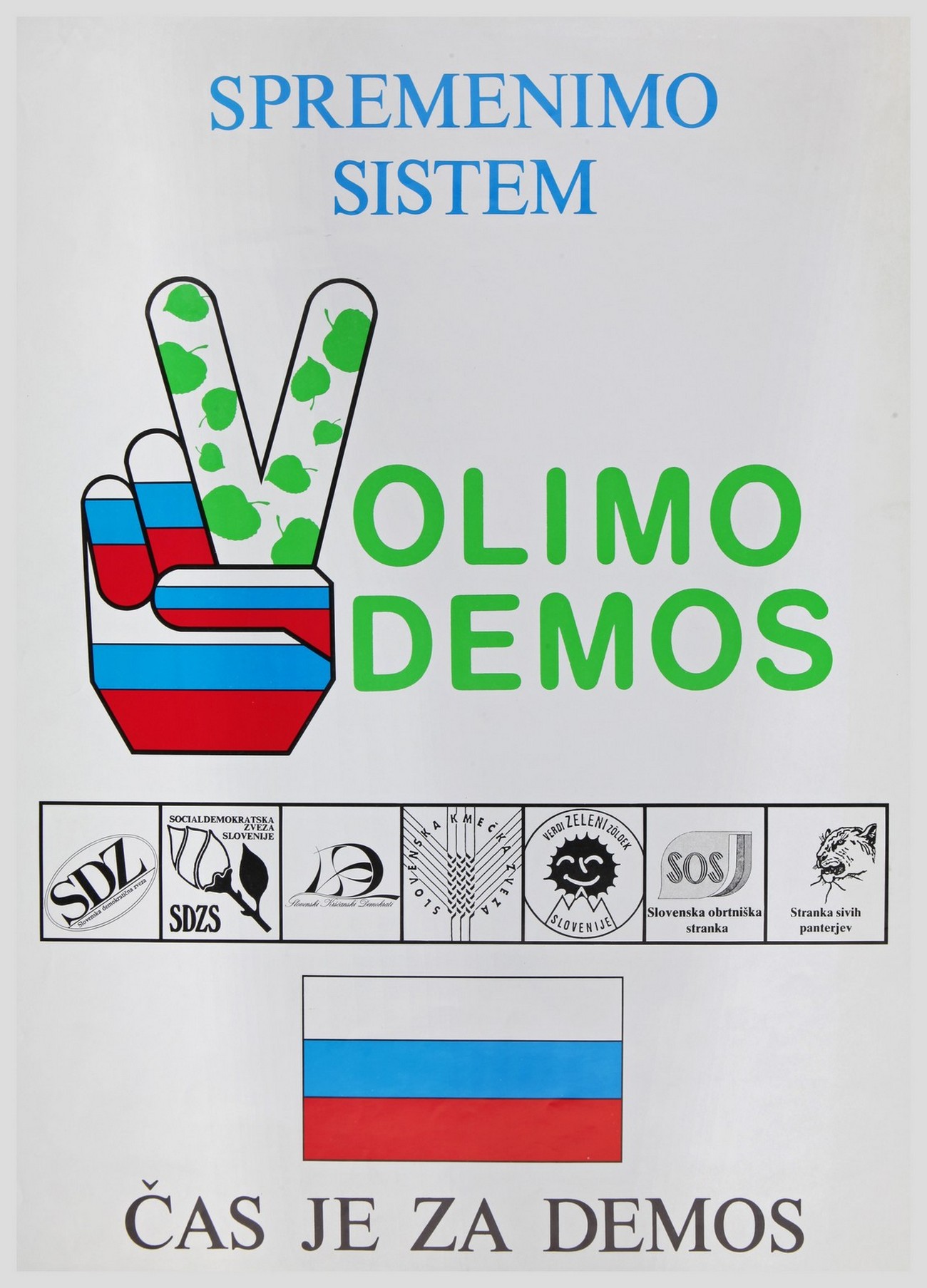

Demos, as this coalition was named, appeared publicly for the first time on 10 December 1989. In the beginning of the following year, on 8 January 1990, it was also joined by the Greens of Slovenia and the Slovenian Peasant Union (which had initially found it difficult to decide between the Demos coalition and the Socialist Youth League of Slovenia). Two smaller parties also joined Demos in time for the election: the Liberal Party (that represented artisans in particular) and Grey Panthers (the pensioners’ party). The coalition was led by the Presidency consisting of two members from each of the parties, and Jože Pučnik was appointed as president. Sovereign Slovenia and parliamentary democracy represented the fundamental points of Demos’s election programme, while a considerable part of its election strategy was based on anti-communism.

After some coordination, the new legislation – the Association Act and the Election Act – was adopted by the Slovenian Assembly on 27 December 1989. They enacted the right to political association. Already earlier, an interpretation of the old legislation by the Assembly’s legislative commission had allowed for the creation of associations (the forerunners of political parties). The new election act was a political compromise, adapted to the existing structure of the Assembly. As such, it represented a combination of the majority system (Chamber of Associated Labour, Chamber of Municipalities) and proportional system (Socio-Political Chamber).

At the beginning of 1990, the formation of the Slovenian pre-election political space was completed. The former associations and socio political organisations transformed into classic political parties. In November 1989, the Socialist Youth League of Slovenia renamed itself as the Liberal Democratic Party (LDS); in February 1990, the League of Communists of Slovenia added a new name to the old one: the Party of Democratic Renewal (SDP); in January 1990, the Socialist Alliance of the Working People renamed itself as the Socialist Alliance of Slovenia; while the Federation of Associations of National Liberation War Veterans remained a non-partisan organisation that quietly supported the communists in particular. Under the pressure of competitive trade union organisations, the former trade unions, which also had the status of socio-political organisations, mostly started focusing on trade union issues.

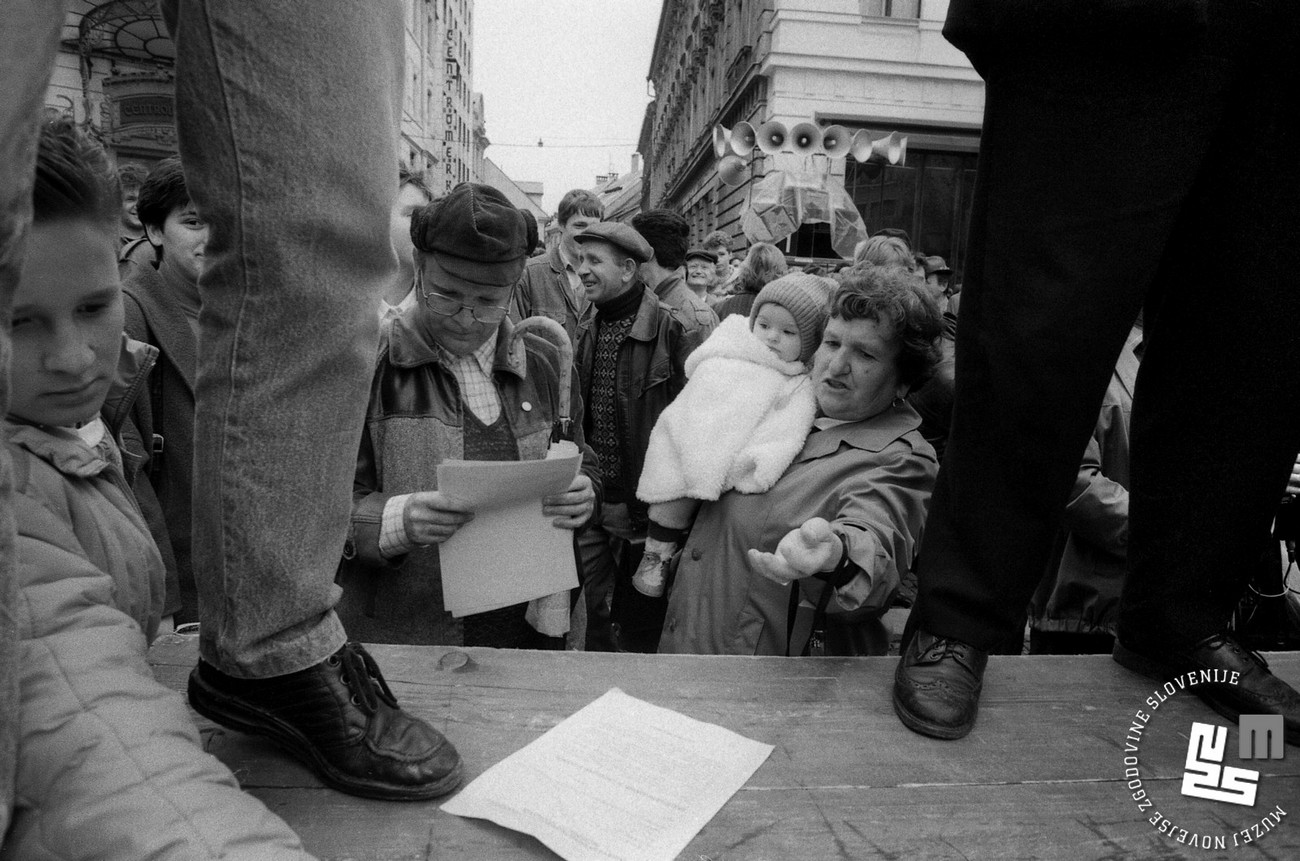

Despite the lack of experience in this sort of activity, the campaign for the first democratic election after World War II proceeded without any major incidents. To this day, the question of whether the contemporaneous media (especially what was, at the time, still the only television station) gave priority to the old political forces remains a matter of individual outlooks and interpretations.

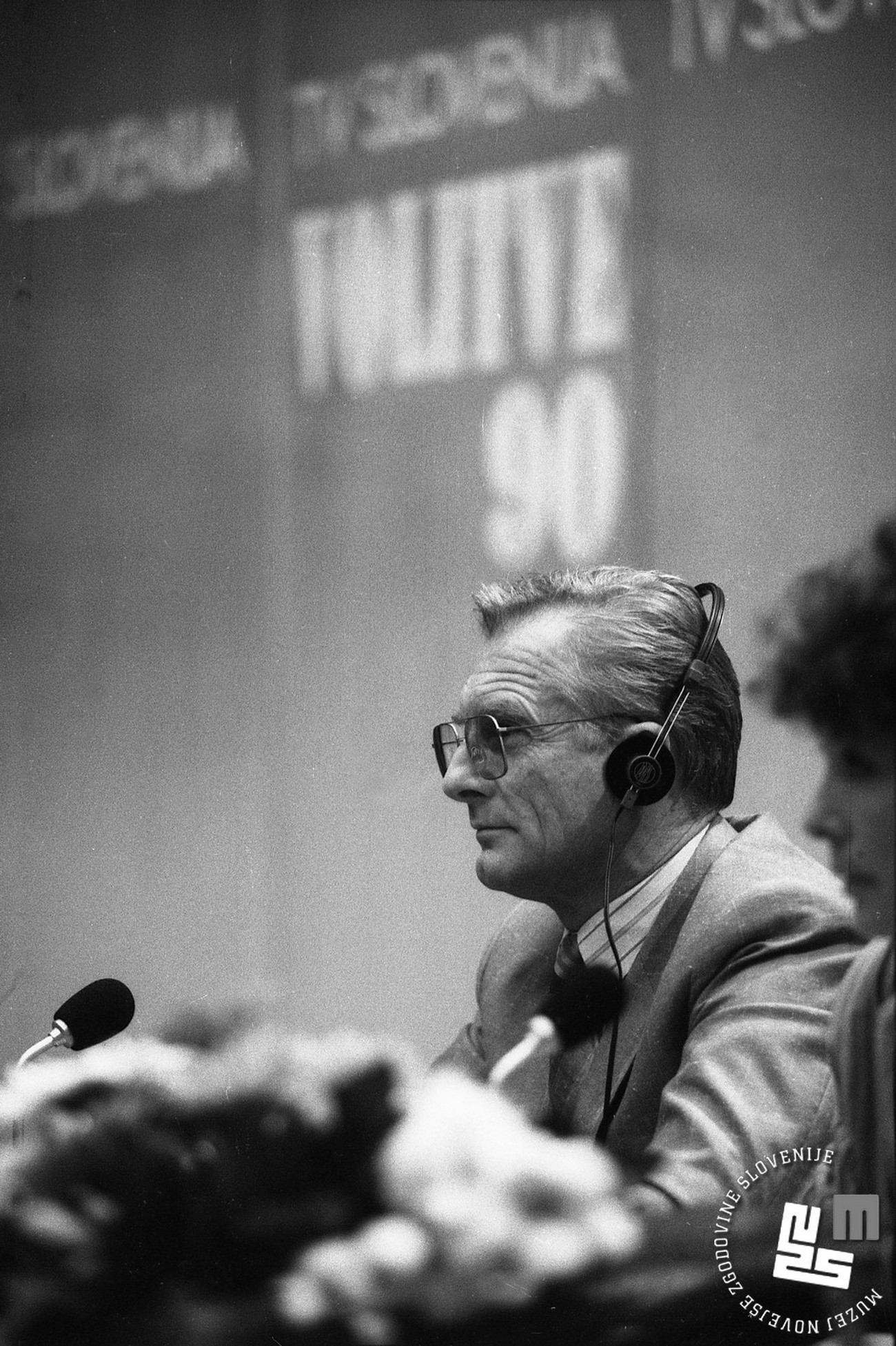

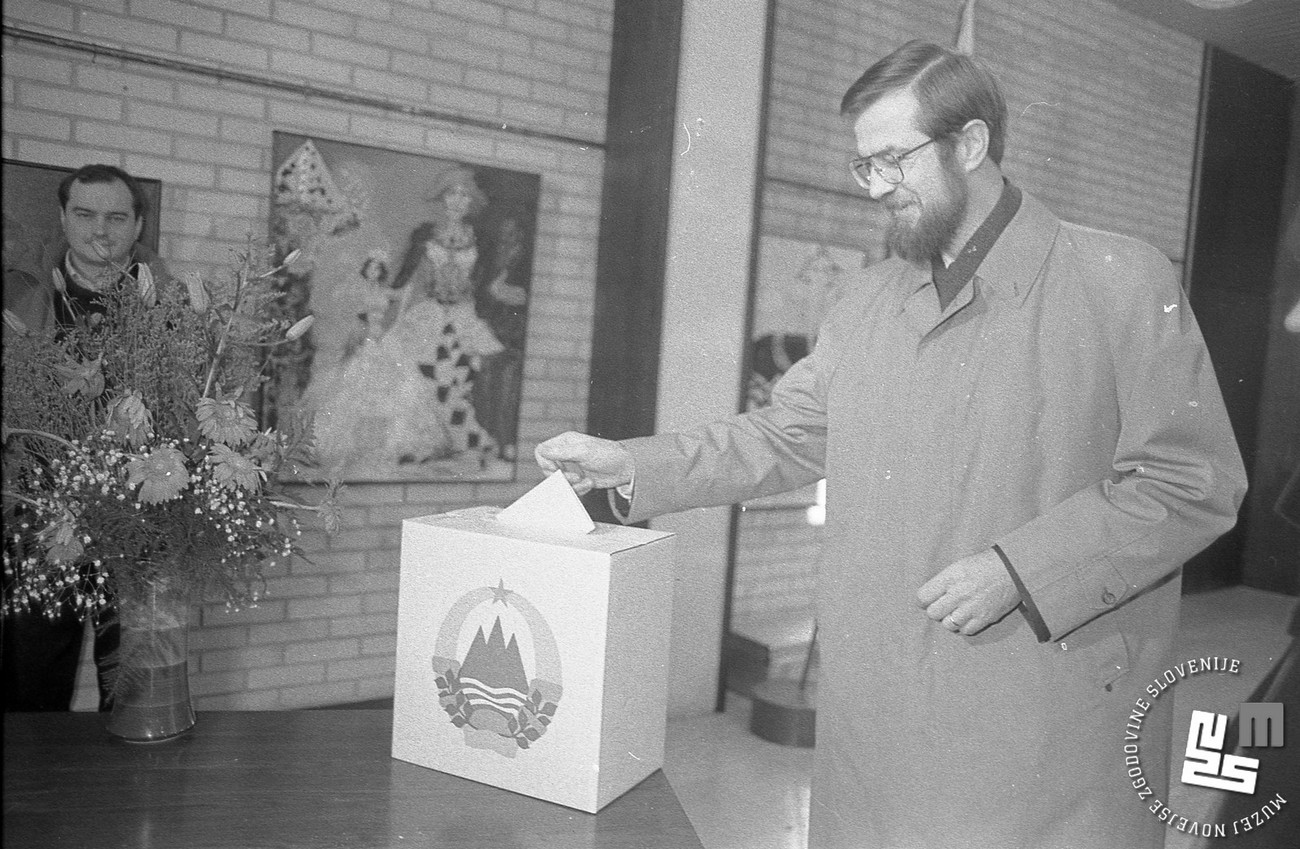

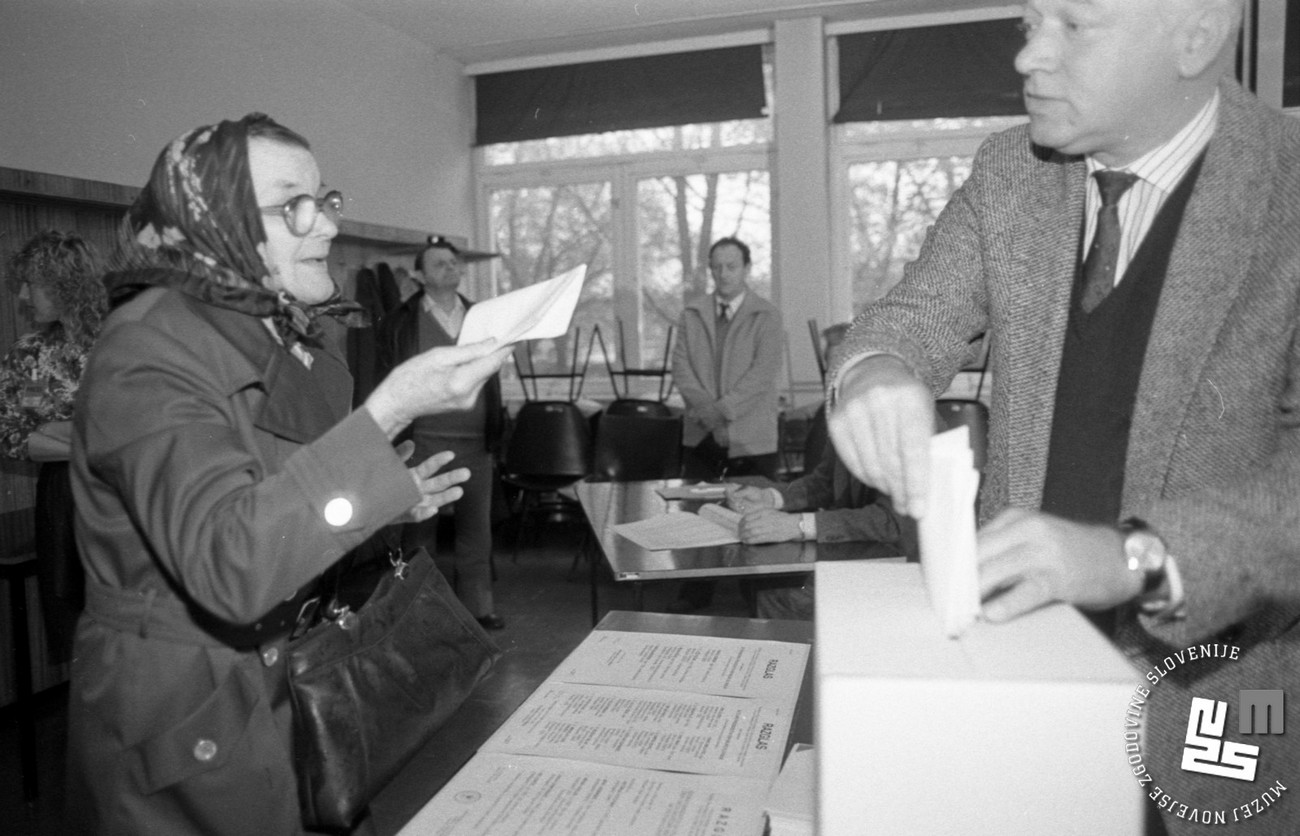

Normatively, the assembly system was still based on the 1974 Constitution, partly “fixed” through the adoption of constitutional amendments. Therefore, the parties proposed candidates for three chambers: the Socio-Political Chamber, the Chamber of Municipalities, and the Chamber of Associated Labour. Each of these consisted of 80 deputies (240 in total). At the election, the Demos coalition won 126 seats, while the League of Communists of Slovenia – Party of Democratic Renewal was the most prominent of the rest of the parties. Ten political parties as well as representatives of both minorities and a few independent candidates got into the Parliament. The voting for the National Assembly, where political party preferences were clear, was of key importance. These preferences were less distinctive in case of at least some of the deputies in the other two chambers because of the specific way of voting.

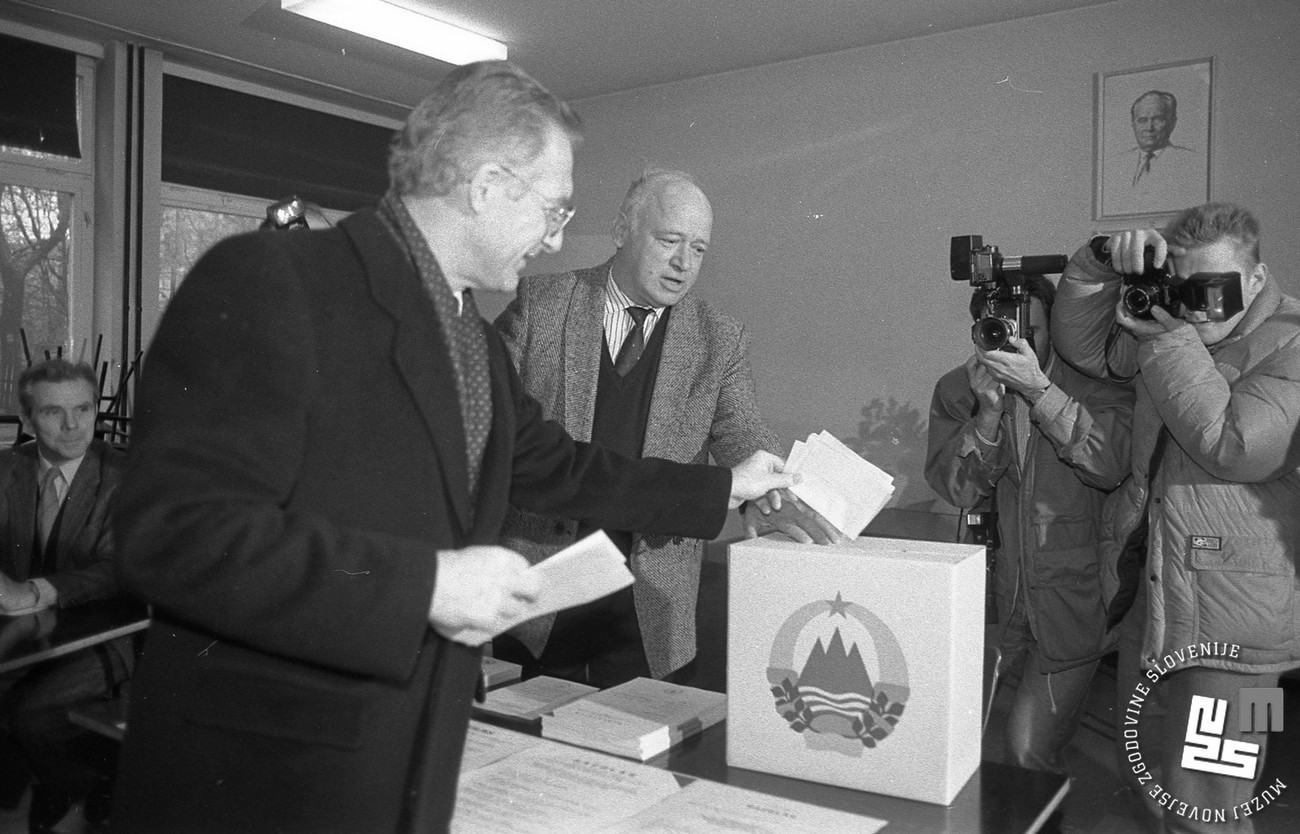

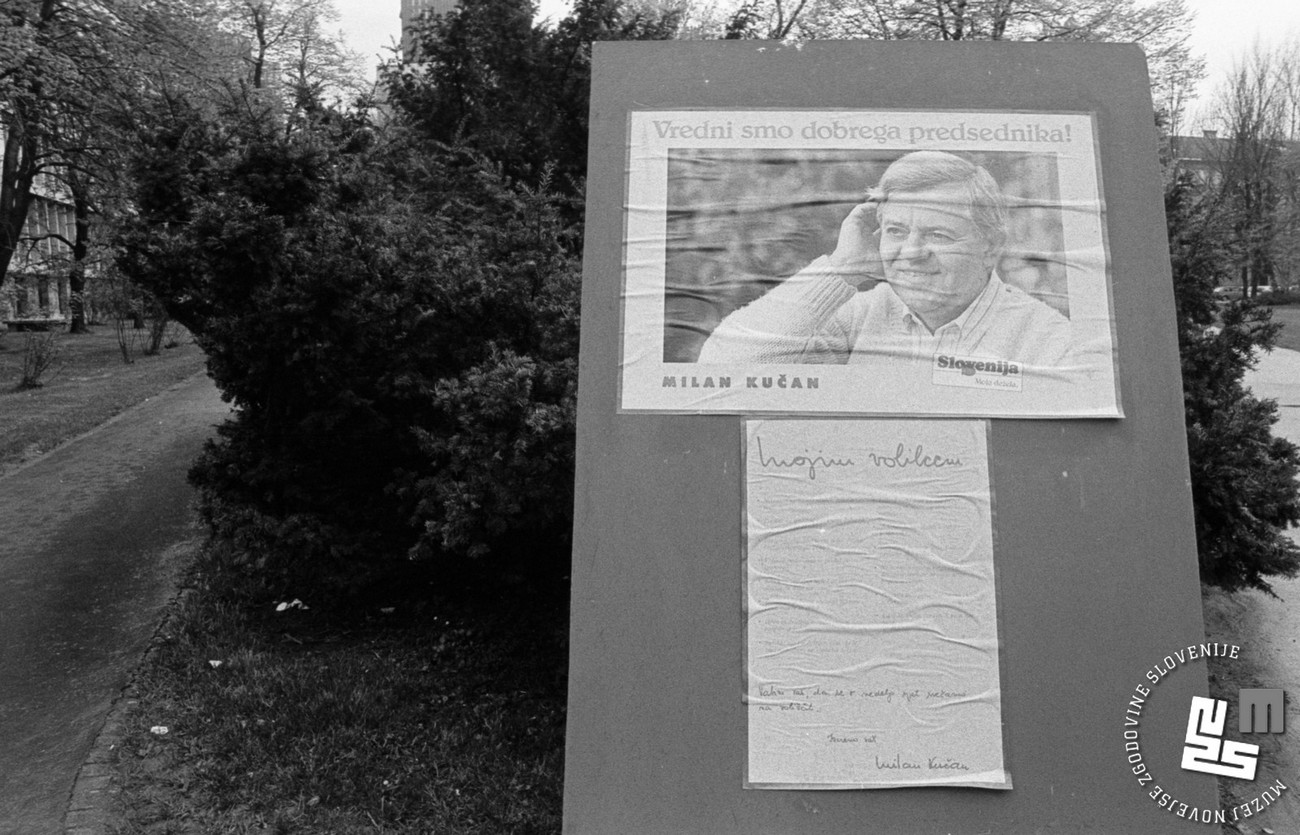

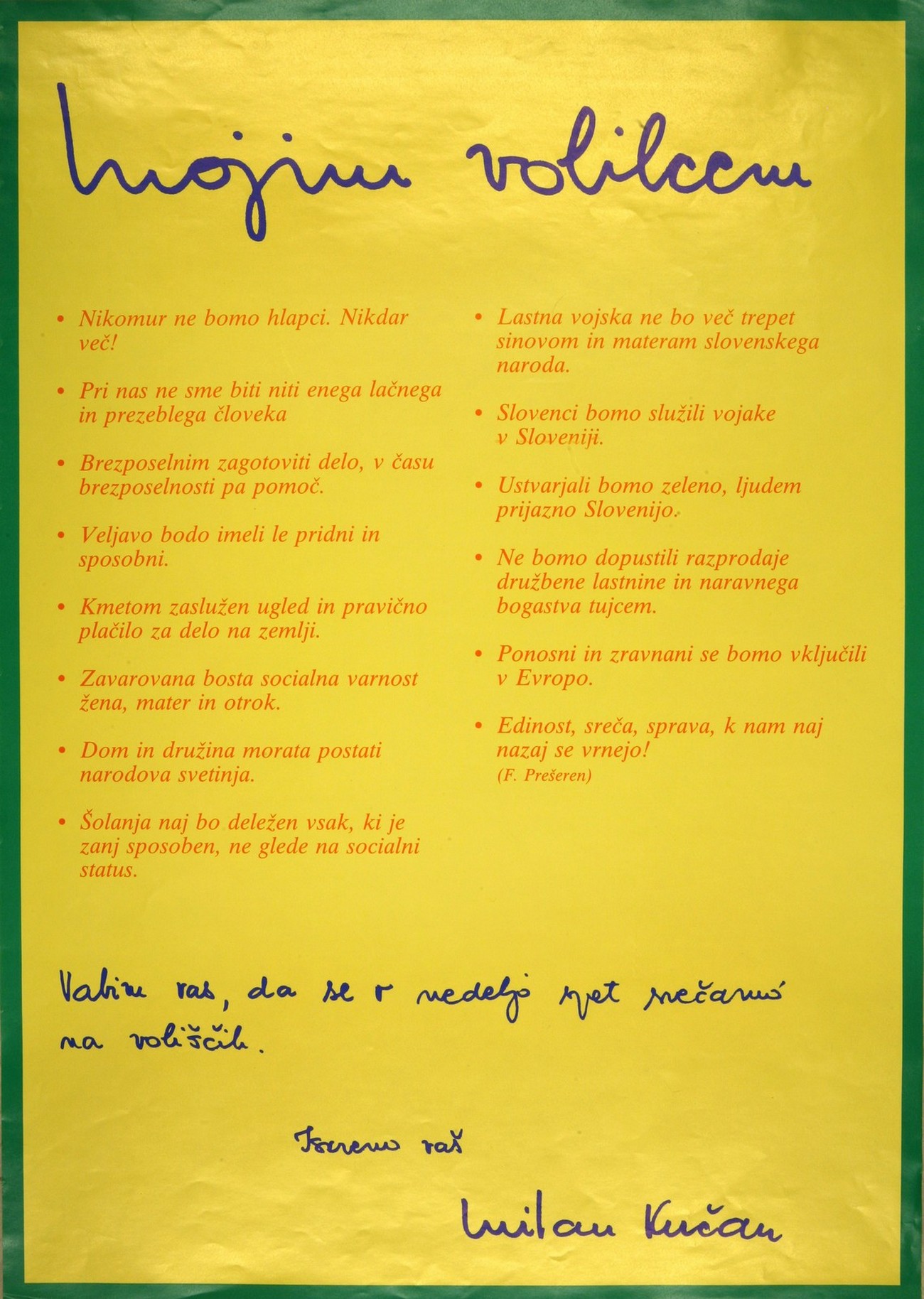

The Presidency of the Republic was elected directly: Milan Kučan became the president, while Matjaž Kmecl, Ivan Oman, Dušan Plut, and Ciril Zlobec were elected as its members. The new Assembly’s inaugural session took place on 17 May. France Bučar became its president. In the past, he had been exposed to serious attacks of the authorities: at the beginning of 1988, he had even been accused of high treason because of his speech at a session of the European Parliament in Strasbourg where he had argued that the West should not provide aid to the “totalitarian and anti-democratic Yugoslavia”. In his inaugural speech as the President of the Assembly, he stated that “with the formation of this Assembly, /.../ the civil war that has fractured and paralysed us for nearly half a century comes to an end”. In July, the state and the Catholic Church confirmed the reconciliation at a solemn symbolic event in the Kočevski Rog forest, in the spot where members of the Home Guard had been executed after the war. However, the handshake between President Kučan and Arch Bishop Šuštar was merely symbolic, as the profound disagreements were pushed to the background only for a short yet momentous period of a few months during the Slovenian emancipation.

The President of the Republic gave the mandate for the formation of the new government to the President of the Slovenian Christian Democrats Lojze Peterle, as the Christian Democrats had received the largest number of votes within the Demos coalition and were thus entitled to this function according to the internal agreement between the parties. The new government, which consisted of 27 members and included a few ministers from the opposition parties, was elected without any significant objections.

The authorities were replaced without any major incidents, though not without small-scale skirmishes. It was a unique situation that had never been encountered before, and the interpretations of jurisdictions varied. The question of prestige was important as well. Demos insisted on the agreed-upon mandatary (despite the internal hesitation regarding Peterle, as Dr Jože Pučnik kept being brought up as a potential mandatary despite the previous agreement). The insistence on this put a stop to the idea of forming a government of national unity, which Kučan considered as a potential solution. According to certain legal and political interpretations, the President was supposed to give the mandate to the individual party that had received the largest number of votes, i.e. the League of Communists of Slovenia – Party of Democratic Renewal, instead of the Demos coalition, formed before the election. However, the League of Communists of Slovenia – Party of Democratic Renewal and its President Ciril Ribičič did not stand much chance of forming a government. Therefore, the government was formed by the Demos coalition, and it included certain male and female ministers from the other political options.